Contents of Summer 2007 Collaborative Solutions Newsletter:

In this issue:

Assessing Our Progress & Celebrating Our

Success

Why

does documentation and evaluation matter in collaborative solutions?

What

kinds of questions can an evaluation help answer?

Community-based

participatory evaluation

A framework

for evaluation of coalitions

Community

Story: a neighborhood organization

Levels

of coalition assessment - tool

Community

Story: national organization with multiple sites

Coalition

Member Assessment - tool

Community

Story: a small non-profit and two communities

Tools

and Resources

Highlights from Tom Wolff & Associates

Assessing Our Progress & Celebrating

Our Success

Why does documentation and evaluation matter in collaborative

solutions?

The

question, how we are doing? often comes up in community work involving

collaborative solutions. Sometimes a coalition’s funders expect

formal evaluations. At other times the question arises when a member

says, “Well,

we have been meeting for months [or years] and what have we accomplished?

Is the community any better off?”

We do often

think that funders are the driving force that impels us to evaluate

our coalition progress. However, if we look carefully we often discover that

our members (especially our grassroots members) are often involved in a regular

evaluation process. They vote with their feet by attending or dropping out

of our community efforts. They participate when they perceive that the coalition

is succeeding at creating change.

Most collaborations

are motivated to engage in an evaluation process because it is required

for their funding. Someone on the outside has decided for them that evaluation

is a necessity. Yet successful evaluations most often occur when the

collaboration itself decides that there are critical questions that must be

answered, such as: After having been at this for three years, are we getting

anything done? Are we being effective? Is the way that we are set up the most

effective? What do all of our members think about what we are doing? These

kinds of questions can motivate a collaboration’s steering committee

and staff to undertake an evaluation process with a high level of interest.

Assessing

our progress and knowing whether we are succeeding is vitally important

to all of us. Yet we know that in most collaborative solution processes very

little evaluation or assessment occurs (Cashman and Berkowitz, 2000). Coalitions

may fail to evaluate their efforts for several reasons: (1) They lack motivation

and interest; (2) They lack access to easy, usable tools for evaluating

both the process and the outcome of the collaborative efforts; (3) They fear

what evaluators might "find"; or (4) They fail to find appropriate

evaluators and set up effective, mutually respectful relationships

with them--relationships in which the data collected are actually useful.

So

why do collaborations become engaged in evaluations? There are some

clear motivations: (1) They want to improve their work and getting

feedback is one proven way to accomplish that; (2) They want to record

and celebrate their successes; (3) They must report on their progress

to a funder, a board, or the community; (4) They are thinking of their

future and issues of sustainability, and a first step in ensuring ongoing

viability is assessment that tells the group which activities to continue

and which to jettison ( http://www.tomwolff.com/collaborative-solutions-newsletter-inaugural-issue.html).

(CADCA, 2006 see Resources).

Page Top

What kinds of questions can an evaluation help answer?

What

activities took place? A process evaluation focuses

on day-to-day activities. Methodologies include activity logs,

surveys, and interviews. Materials to track can include in-house

developments, outside meetings, communications received, community

participation, and media coverage. Surveys can rate the importance

and feasibility of goals and the satisfaction of members. Process

evaluation can also analyze critical events in the development of the

collaboration. Process evaluation helps a coalition see the

strengths and weaknesses of its basic structure and functions.

What was accomplished? An outcome evaluation focuses

on accomplishments. It can include changes in the community

(the number and type of shifts in policies or practices) as

well as the development of new services. It can also involve surveys

of self-reported behavior changes, rating the significance of outcomes

achieved. The number of objectives met over time is a useful evaluation

tool.

What were the long-term effects? An impact evaluation focuses

on the ultimate impacts that the collaboration is having on the community,

over and above specific outcomes. The focus here is on statistical

indicators of population-level outcomes. For example, a teen pregnancy

collaboration might focus on the pregnancy rate for its community.

Page Top

Community-based participatory evaluation

Once

the results have been collected and reports written, the collaboration

must actively disseminate the findings to the community so that its

members can look at the data, decide what changes are necessary in

response to the findings, and change or adapt the strategic plan

and the collaboration’s activities in response to the results

found in the evaluation.

In

order to satisfy the coalition’s interests, the evaluations

must be both methodologically sound and intimately involved with the

organization. Too often our evaluation processes and instruments are

developed and implemented by outside evaluators. Coalition members

only see the information many months or even years after it is collected,

when final reports are prepared for the funder.

In

collaborative solutions processes, we strongly advocate for close working

relationships between the evaluators, the coalition staff, and the

community. You cannot learn from evaluation results that are not fed

back to you regularly. Nor can you celebrate successes in a timely

manner. You cannot develop a sustainability plan unless all coalition

members have access to evaluation information. So when we work in collaborative

situation we not only have to develop appropriate evaluation mechanisms,

we have to develop whole new ways for the community to engage in the

process.

Page Top

A

framework for evaluation of coalitions

Evaluation of coalitions is complex. The field and the literature

are evolving and new research documentation systems and tools emerge

on a regular basis. There are questions about what to measure and how

to measure the process and the various levels of outcomes (Wolff, T.

A Practical Approach to Evaluating Coalitions http://www.tomwolff.com/resources/backer.pdf)

One of the best models for evaluating coalitions comes from the Work

Group for Community Health and Development at the University of Kansas

(http://communityhealth.ku.edu/).

Based on the Institute of Medicine’s framework for collaborative

public health action in communities (2003), this evaluation model is

described below. It’s easy to see that this model would apply

not just to the coalition-building work of organizations but also to

other systems-change agendas.

A framework for collaborative public health

action in communities.

(Source: CDC, 2002; Fawcett et al., 2000; Institute

of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, 2003.)

The

model for participatory evaluation developed by Fawcett and

Schultz (2007) is made easier through customized Internet-based

Workstations that include online supports for documenting and

analyzing accomplishments, graphing, and reporting (Fawcett

et al, 2003). It provides clear pathways for understanding the

change processes involved in collaborative solutions, and therefore

for understanding the evaluation questions that follow. In most

efforts that involve collaborative solutions, we are working

with multiple factors that produce multiple and interrelated

outcomes. No single intervention--no one program or policy change

targeting one behavior--is likely to improve population-level

outcomes. Often there are long time delays between a collaborative’s

actions and the resulting widespread behavior change. So it

is difficult to assess whether any effort, or combination of

efforts, is bringing about change. And of course the most important

thing we want to know is whether our efforts are producing change.

With the KU Work Group’s participatory evaluation model (Fawcett, et al.,

1995; 2000; 2003; 2004), groups document new programs, policies, and practices,

along with the community and systems changes that are the critical components

of the coalition effort. Programs, policies, and practices—changes

in communities and systems-- are central to this model. If we think about

it, these three really do capture the intermediary changes that most of us see

along the path to community change. Say we are looking to reduce the level of

smoking in a given community. Before we can measure the population-level reduction

in smoking, we can document that we've put smoking-cessation classes in place,

smoking-prevention programs in the schools, policies on smoking cessation in

workplaces, and policies to ban smoking in restaurants. We can also document

changes in smoking behavior (practices) in multiple settings (schools, work,

entertainment). Documentation of these types give us an excellent intermediary

way to measure a coalition’s success long before we can document the change

in smoking levels in the community as a whole.

The KU Work Group’s participatory

evaluation framework (Fawcett et al., 2004; Institute of Medicine, 2003),

detailed below, proposes a general model with evaluation questions

related to the five phases of the IOM model.

Overall question: Is the initiative serving as

a catalyst for change related to the specific goals?

Evaluation questions at each of the five phases are:

- Assessment and collaborative planning

- How has the coalition developed its organizational capacity?

- Does the coalition have a vision and a plan for community mobilization?

- Is the coalition membership inclusive of all community sectors?

- Targeted action intervention

- Has the coalition developed measurable and targeted action steps?

- Is the coalition taking actions to reach its goals?

- Will these action steps help the coalition reach its goals and meet its objectives?

- Community and systems change

- Does the coalition create community changes, defined as changes in programs,

policies, and practices?

- Have participating organizations changed programs, policies,

and practices? (These are the intermediary outcomes

that seem to be able to predict the ultimate population-level

change).

- Widespread behavior change

- How widespread is the change?

- Where have these changes occurred and what form do they take?

- Are changes happening in many sectors and systems?

- Improvement in population-level outcomes

- How are community/system changes contributing to the efforts to improve

the community?

- Are community/system changes associated with improvements in population-level

outcomes?

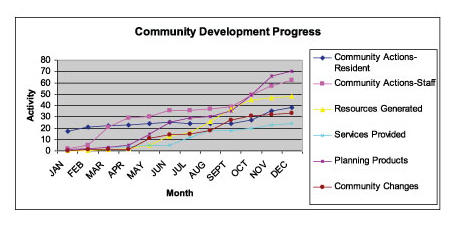

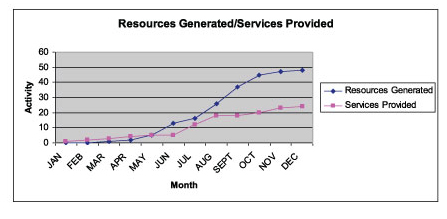

The chart above plots out both community changes (policies, practices,

programs)

and population-level outcomes. The relationship of the curve changes

for these

measures is one way of getting attribution.

Although this model was especially

developed around health issues, it generalizes quite well to most

types of community change (see Fawcett et al, 2004). Thus, an ultimate

population-level outcome may be the level of smoking in a community

and level of smoking-related illness (for a health-related concern)

or it may be the level of violence, or the level of access to adult

basic education for immigrants (for social concerns).

Page Top

Community Story: A

Neighborhood Organization, Documentation/Evaluation

The

best way to show you what we mean is to tell you about some of the work we

do with coalitions and communities. We get called upon to conduct or assist

with evaluations in many ways. On the most basic level, we work with grassroots

neighborhood groups who need to track their successes for themselves and

their stakeholders. On a larger scale, we are contracted to evaluate national

coalition-building programs with numerous sites across the country. In both

cases, the core question is what information will help the coalition grow

and be able to demonstrate its accomplishments to its members and its stakeholders.

With the

Cleghorn Neighborhood Center (CNC) in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, we helped them

shift their mission and work from a service framework back to its roots in

community development and community organizing. It received funding from the

Community Foundation of North Central Massachusetts and a green light from

its board for this shift. Following this change, both the coalition and the

foundation needed to see whether the new plan was really going to work. Because

little community development work was occurring in the neighborhood, how to

asses the new approach was a mystery for many in the area. Community development

was also new territory for the staff, so we designed a documentation process

that would help the staff stay on track at the same time as they recorded

their progress.

We adapted the University of Kansas’ Online Documentation

and Support System (for information on purchasing these services go

to the KU Work Group’s website: http://communityhealth.ku.edu/services/services.shtml/ ).

This is based on the Ku Work Group’s efforts to provide

the grassroots group with a low-cost/no-cost tracking system. The staff

defined and logged activities, recorded number of people involved,

and tracked resources generated, planning products, services provided,

community actions by staff and residents, and community changes. (See

definitions below). As a result of these records, CNC was able to provide

charts and commentary in its report to its funder and its board .

Below

is an example from a CNC report/grant application:

The CNC used the Kansas Documentation System as a tool

to document and evaluate its community development activities. This

tool has been used by such organizations as the Centers for Disease

Control, the MacArthur Foundation, and the Kansas Health Foundation.

Log – All community development activities were tracked by

entries in a comprehensive log. Ninety-four activities were documented

by the CNC during the past year. The log entries provide a view of

both activities and community response.

Documentation system – This system was used to track community

changes that were created by community coalitions and community development

activities. The logged data and other information tracked the progress

of the initiative in relation to the following variables, which are

defined below:

Community Actions--Residents: Activities aimed at community

change completed by the volunteer group outside of CNC.

Community Actions--Staff: Activities aimed at community change

completed by CNC staff.

Resources Generated: New services, funds, or materials generated by

resident volunteers

and staff.

Services Provided: Activities by the resident volunteers that occur

in the CNC.

Planning Products: Creation of task forces, mini-grant applications,

recruitment, PEP, etc.

Community Change: Policy, practices and procedures (PPP) in the community

that assist the CNC in reaching community changes (i.e. cleaner neighborhood)

Increases in community activities and community changes continue

to be most critical to CNC’s efforts. The tables below indicate

the greatest increase in three major areas--planning products, resources

generated, and community actions--residents. There is a steady, but

lesser, increase in community actions--staff, services provided,

and community changes. The table reflects that during the first six

months of the project, internal capacity was built by hiring staff,

reaching out to the community, and structuring next steps. The progress

increased in June after the community meeting where volunteer groups

came together to address community issues.

Total Community Progress

Chart

1

Charts broken down by category

Chart 2

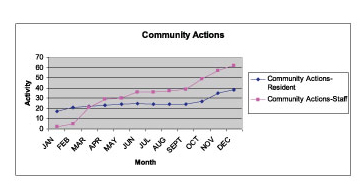

Community Actions--Residents – The most frequent activities

measured were actions by community residents. Examples of this category were:

resident-led street clean ups, bi-weekly resident meetings, GED and PEP classes,

and International Food Night. This illustrates that mobilization efforts

were very effective, resulting in residents increasingly acting to improve

their neighborhood.

Community Actions--Staff – The graph reflects the role of staff

as catalysts, with community residents’ roles as leaders. The high level

of residents’ activities has been a positive challenge to the staff.

Chart

3

Resources Generated – Reflected in this graph is the level of

new, local resources that were raised as a match to Community Foundation’s

funding. Examples included residents:

- Donating time as skilled computer technicians to fix equipment

- Writing newspaper articles on the neighborhood changes and the newsletter

- Earning funds to supplement staff and program salaries

- Assisting with building maintenance

- Fundraising on behalf of the center to supplement programming expenses

Services Provided – Traditionally, these would have incorporated

the CNC’s food pantry, clothes closet, and translation services. However,

thanks to the efforts of the community development process, new services have

emerged, which include:

- Residents meetings

- Yard sales that are coordinated by residents

- Thanksgiving donations

The above services originated in the CNC and were identified by the resident

volunteers.

Chart

4

Planning Products – The graph shows the development of appropriate

planning products to move the community development process along. These included

the creation of resident working groups, such as the Parent Initiative, the

Traffic Safety group, and the Community Activity groups. It also included staff

and consultant ongoing planning.

Community Change – This graph shows that community changes have

occurred as an outcome of community actions. Below are examples of new community

changes that have resulted from the CNC community development process:

- Cleghorn is cleaner

- Relationships with residents (CNC to Resident and Resident to Resident)

have been built

- The CNC has been successful in advocating for residents (discrimination

issue)

- There is more police presence in the neighborhood

- More first-time voters are registered

- Residents of different ethnicities have been brought together in celebration

Although this project is still in its infancy, the successes to date have laid

the foundation for continued growth. The Cleghorn neighborhood and the residents

involved with the Cleghorn Neighborhood Center are becoming a catalyst for

community change. This change will lead to a revitalization of the historic

Cleghorn Neighborhood and will simultaneously engage and empower its residents.

Ultimately, we are looking for changes in policy, practices, and procedures

in the community; an increase in Latino leadership; and a strategy to be implemented

to bring diverse people to the table.

Ref. Cleghorn Neighborhood Center Grant

Submission

Page Top

Many levels of coalition assessment

When we set out to document our collaborative solutions work, we have lots

of choices as to what we will look at and what we will measure. We can ask

mainly internal-process questions about whether the coalition has the members

and core processes that it needs. We can ask about relationships and changes

in relationships, which emerge as both process and outcome components critical

to a collaborative’s

success. Finally, we can ask about the various levels of outcomes, or end results.

A Level

of Coalition Assessment Tool has been developed that describes

the range

of questions we can choose from when we document our coalitions’ work. We

use this list to help clients decide what they want to learn about through

documentation and evaluation. In a collaborative participatory evaluation process,

the members of the coalition and the community can review these questions to

decide what is most important for them to know. This helps ensure that the

evaluation is aimed at the key needs of the coalition’s members.

Page Top

Community Story: National Organization with Multiple Sites-Documentation

and Evaluation

One example of the use of a list

of levels of assessment, like the one referenced

above, involves our work with a federal project with

17 sites covering the nation. In the last year, we were asked to evaluate the

progress of each of the 17 networks on its collaborative ventures. Our efforts

have involved a number of steps. We started with the list of questions on the

levels of assessment to help us all understand what the federal agency and

the networks wanted to assess. The evaluation ultimately included a review

of the work to date; the development and completion of oral interviews of the

17 directors and staff; and the development of an online Coalition Member Assessment

form.

Coalition Member Assessment Tool

The

Coalition Member Assessment Tool is a variation of earlier satisfaction

surveys (http://www.tomwolff.com/resources/backer.pdf -

see Gillian Kaye, Steve Fawcett instruments) that allow members

to rate their coalition on a 1-5 scale, from agree to strongly disagree.

The instrument has 44 rated questions and a few open-ended questions. It covers

the following areas:

Vision – planning,

implementation, progress

Leadership

and membership

Structure

Communication

Activities

Outcomes

Relationships

Systems

outcomes

Benefits

from participation

Open-ended

questions

The

Coalition Member Assessment lends

itself to online survey mechanisms (Survey Monkey at www.surveymonkey.com,

Zoomerang at www.zoomerang.com)

that make it easy to administer the survey and tabulate the results.

Page Top

Community Story: A Small Non-Profit and Two Communities, - Documentation

and Evaluation

Another evaluation story involves our work with a

small substance-abuse agency in upstate New York where we helped them to

track their development work in two struggling communities. This evaluation

was designed to allow the staff, which was untrained in evaluation, to conduct

the evaluation themselves and to feed back data to the community on a regular

basis. A notebook was developed that included logs of all activities undertaken

by the coalition (staff and community members), minutes from meetings, records

of meeting attendance, and copies of all community press coverage. Most coalitions

ordinarily keep this type of information, so it could easily be channeled

to produce the core data for both process and outcome evaluations.

One

of the goals of the coalition was to create leadership. The attendance and

logs were examined to document moments when community members took a leadership

role. These were charted.

The

regular logs of activity were analyzed through a system developed by the University

of Kansas (Fawcett et al 1995; 2000; 2003; 2004) to document collaborative

outcomes. The initiative documented services provided, planning products, resources

generated, community actions, and community changes. These variables were charted

in a cumulative graph.

A

format was created for evaluating all training opportunities for community

members, and finally a member-satisfaction survey and follow-up interviews

were implemented.

All

of these were pretty straightforward mechanisms. They were implemented by a

local staff person who had little background in evaluation but worked with

care and produced a highly successful notebook. The notebook provided a clear

picture of the coalition’s activities and successes. As the data emerged,

it was regularly shared with coalition members at their monthly meetings. The

community participants found the information useful and the completed notebook

provided impressive coverage of the coalition’s activities for the large

foundation that was supporting its work.

This project

offers a wonderful example of how a consultant can build the client’s

evaluation capacity instead of doing the evaluation. One advantage of this

approach is that evaluation can be easily integrated into the coalition’s

daily work—both gathering information and immediate use of the findings.

In this case, the staff person regularly shared evaluation information with

members as it emerged. Another advantage is that the sponsoring organization

ends up with a staff person who has new evaluation skills.

Page Top

Conclusion

We hope

that this issue of the Collaborative Solutions Newsletter will help our readers

feel more comfortable and less intimidated with the idea of assessing progress

and celebrating successes. We hope to help coalitions feel that they are able

to proceed with documentation and evaluation of their collaborative efforts

on their own.

Documentation

and evaluation are important. They allow you to understand where your coalition

is going; what your members feel about the direction; and whether, indeed,

you're making a difference.

Documentation

and evaluation of collaborative efforts is understandable and do-able. It does

not have to be a mystery. It does not have to call up old math anxiety. It

can simply involve asking the key people the key questions.

Documentation

and evaluation can help your coalition answer critical questions about your

efforts. Are you all clear on where you are headed? Do you have a viable structure?

What changes are you really creating? Is your progress steady?

Documentation and evaluation, when done in a participatory manner so that the

coalition and not the evaluator is in charge, will help your coalition grow.

Page Top

References:

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). (2002). Syndemics overview:

What procedures are available for planning and evaluating initiatives to prevent

syndemics? The National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Syndemics Prevention Network. Available online at www.cdc.gov/syndemics/overview-planeval.htm.

Accessed June 13, 2007.

Fawcett, S.B., Francisco, V.T., and Schultz, V.T. (2004). Understanding and improving

the work of community health and development. In J. Burgos and E. Ribes (Eds.),

Theory, basic, and applied research and technological applications in behavior

science. Guadalajara, Mexico: Universidad de Guadalajara.

Fawcett, S. B., Francisco, V. T., Hyra, D., Paine-Andrews, A., Schultz, J. A.,

Russos, S., Fisher, J. L., and Evensen, P. (2000). Building healthy communities.

In A. Tarlov and R. St. Peter (Eds.), The society and population health reader:

A state and community perspective (pp. 75-93). New York: The New Press.

Fawcett, S.B., Schultz, J.A., Carson, V. L., Renault, V.A., and Francisco, V.T.

Using Internet based tools to build capacity for community-based participatory

research and other efforts to promote community health and development. In M.

Minkler and N. Wallerstein (Eds.), Community based participatory research for

health (pp. 155-178). San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Fawcett, S. B., Sterling, T. D., Paine-Andrews, A., Harris, K. J., Francisco,

V. T., Richter, K. P., Lewis, R. K., and Schmid, T. L. (1995). Evaluating

community efforts to prevent cardiovascular diseases. Atlanta, GA: Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention

and Health Promotion.

Institute of Medicine. (2003). The community. In The future of the public’s

health in the 21st century (pp. 178-211). Washington, DC: National Academies

Press.

Page Top

Tools and Resources:

How to

purchase participatory evaluation services and online supports from the

University of Kansas Work Group for Community Health and Development: The

KU Work Group can build and provide technical support for a customized Online

Documentation and Support System for your initiative (Link

to below and link to KU Work Group’s website http://communityhealth.ku.edu/services/services.shtml/

Building Healthy Communities – Lessons and Challenges,

Berkowitz ,B.& Cashman,S, Community 3(2), 1-7 2000

CADCA Report Drug-Free Communities Support Program

National Evaluation.– 2006 National Evaluation of DFC (Drug

Free Communities) Program Shows Successful Coalitions Exhibit Similar Characteristics

National Coalition Institute Research into Action April1,2007 Office of National

Drug Control Policy. (2007). Annual findings report 2006: Drug-Free Communities

Support Program National Evaluation. Battelle & the Association for

the Study and Development of Community. Click

here to download the 2006 Annual Findings Report.: http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/dfc/evaluation.html

Monitoring and Evaluation of Coalition Activities and Success by

Stephen Fawcett, David Foster, and Vincent Francisco. Chapter in From

the Ground Up: A Workbook on Coalition Building and

Community Development by Tom Wolff and Gillian Kaye.

1994 http://www.tomwolff.com/healthy-communities-tools-and-resources.html

A practical approach to evaluating coalitions. Tom Wolff

in Backer,T. (Ed.)

Evaluating

Community Collaborations. Springer Publishing, p57-112, 2003.

Studying the Outcomes of Community-Based Coalitions, Berkowitz,

Bill

In The Future of Community Coalition Building American Journal of Community

Psychology Vol. 29, no.2, 213-228, 2001

Page Top

Highlights of recent work by Tom Wolff & Associates

The last six months have been an especially productive and busy time

for Tom Wolff & Associates. We are delighted to have been engaged

in exciting work with numerous organizations at local, state, and national

levels.Some highlights are noted below:

Boston College: Building community – university relationships

to increase capacity regarding substance-abuse prevention.

Boston’s REACH 2010 program: Disparities in breast and cervical

cancer among Black women. Ongoing consultation and training focused

on sustainability.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Ongoing support to the

Strategic Partnership for Change coalition building efforts of the

End Stage Renal Disease Networks within CMS. Consultation, training

and program evaluation.

Cleghorn Neighborhood Center: Ongoing consultation to grassroots neighborhood

organization.

Enlace, Holyoke: Building the Next Generation of Latino Leadership

in Holyoke.

Coordinating all existing community coalitions for the benefit of the

community.

First National Conference for Caregiving Coalitions--Creating

a Legacy: Sustaining Your Efforts, March 2007, Chicago, IL.

Healthy Wisconsin Leadership Institute--Creating a Legacy: Sustaining

Your Efforts, April 2007, Madison, WI.

Highland Valley Elder Services: Consultation--building community assets

in elder communities and elder housing.

Kansas Health Foundation 2007 Recognition Grant Conference: Collaborative

Solutions for Communities. What do we think and know about Collaboration?

April 2007, Wichita, KS.

Society for Community Research and Action: Creating and planning the

First Community Psychology Practice Summit.

Wyoming Tobacco Coalitions: Building and Sustaining Wyoming’s

Tobacco Coalitions, April 2007, Casper, WY.